The poorest soils for the vineyard

Emilio Barco and Luis Vicente Elías, in the aforementioned work, gave an extremely accurate description of the different profiles of viticulture in Quel, starting with the areas in which vines were planted and covering the methods and techniques used in the course of history. And, as is the case in many localities of the Rioja Baja, the authors point out that the poorest soils were used for the vineyards, leaving the better quality land for grain and the irrigated land for fruit crops. Moreover, greater value was placed on the soils closest to the wineries and less importance was given to those areas nearer the hills, given the complications in getting there, working the land and, after the harvest, taking the grapes to the caves.

The “dirty soil” made up of stones and gravel was the most highly appreciated. However, in actual fact, there was practically no sampling of the vineyard soils and, as a result some of the best vine growing land was used for other crops. According to the ‘Atlas del Cultivo Tradicional del Viñedo en España’ (Atlas for the Traditional Cultivation of Vineyards in Spain) the composition of the soil on the “Peña del Marlo” cliff produced the best fruit, followed by the “Peña Dulce” cliff, which was softer and looser and offered poorer grapes. Although the area of Las Coronas, which looked down on the Barrio de las Bodegas winery district, was highly appreciated, in general the vineyards were located in those farming areas with the poorest quality land.

///CLICK HERE IF YOU’D LIKE TO FIND OUT MORE

Barco and Elías conducted a survey among the old growers in the area of Quel, directed at obtaining the most accurate picture possible with regard to the methods and techniques that they were using to work the vineyard, both with regard to what they were doing and also what they knew about previous generations thanks to what they had heard from their elders. The authors indicate that the formulas used were those of the early 20th century when vineyards in La Rioja were restructured following the phylloxera crisis. New cultivation techniques were brought in, largely due to the need to use grafts, something which eventually transformed viticulture in La Rioja.

All vineyards were in rows that were spaced seven foot apart (one and a half metres) in order to use horses. One of the traditional tasks was hilling, consisting in removing the earth around the base of the vine and then using this soil to make two ridges around the vine with a thickness of some 35 centimetres. At times, depending on the planting system used, there were four ridges arranged around each vine.

Until the nineteen-thirties, there were lines with a grid of seven by seven foot, giving a width of 150×150 square. Formerly a “staggered” formula was used, with the same distances but with a rhombus shape for the purpose of making it possible to use the ‘Arabuey’ or X-shaped ploughing system, frequently used on slopes to ensure that the earth from the top of the vineyards did not go to the bottom, thereby preventing the dreaded erosion and run-offs.

In the early days, planting was done in furrows. The earth was prepared with the horse-drawn “Brabant” plough and then, from that moment onwards, only harrows were used to work the land. The authors detailed this work as follows: «With the ‘Brabant’ or swing-over plough, a furrow was made and this was completed with the manual work of the hoe and, in early winter, a hole of up to 50 centimetres deep was made at the planting points. At the beginning of spring, after pruning, the “barbudas” were planted, these were cuttings taken from mother vines and put to root in vegetable patches and places with extremely fertile soil. These shoots were planted deep in the earth, making ridges around them, for protection until rotation. The following year the graft was planted with shoots taken from the best plants on the estate. At that time, these were generally Garnacha or Miguelete, without forgetting other white varietals that have now disappeared.»

With regard to the density, during that period in Quel, the surface area of the arable land was measured in fanegas of 2,278.32 square metres. However, in the case of the vineyard, it was valued at the number of vines in relation to the field work required for the said crop. In the book entitled ‘La elaboración tradicional del vino’ (Traditional winemaking) by Luis Vicente Elías, the author explains that there were different units of measurement:

«The measurement was made by the number of vines, and it varies according to area. In the Rioja Baja it is known as “peonada” and it has from 150 vines in Igea to 200 in Arnedillo or 250 in Aldeanueva de Ebro, with some cases in which the peonada can be as high as 300. In the Rioja Alta it is called “obrada” and varies from 150 in Najerilla to the 200 of San Vicente de la Sonsierra». In Quel, the “peonada” was 200 vines, so that three and a half peonadas were equivalent to the fanega of 17.50 hectares. Although there are also records of four “peonadas”, understanding that this would be equivalent to twenty per hectare. Barco y Elías pointed out that, with these figures, the number of vines per hectare in Quel was 4,000 and this tallies with the yields «that are much lower than those of today».

In spring, the ridges around the vines were removed and the hollow was filled in. This hollow around the vines allowed the winter rains to accumulate there, as well as the manure from cattle or sheep, which was tossed into the hole every two years, considering that this would increase the alcoholic strength of the wine. This work could continue up to the month of May, and then no further work would be done at the vineyards until autumn.

It appears that horse-drawn ploughs became widespread in the vineyards in Quel around 1930 and, although the local blacksmiths were capable of making the most common implements, the “Jaen” and “Garraminchu” ploughs were brought from blacksmiths located in Estella (Navarra). Furthermore, the harnessing of the horses was described. Unlike other winegrowing areas, this was made with a yoke around the animal’s neck and was connected to the plough through straps and chains; this area of La Rioja did not plough with two shafts.

When horses were used to work the vines, the distance between rows was increased to give them more room, as the seven by seven foot layout was too narrow. A plough called the “borracho” (drunkard) was used to remove the weeds close to the trunk. In June the task of “levantar polvo” (raising of dust) was performed, consisting in removing the surface weeds and the ploughing was made after the pruning, with seven or eight furrows between the vines. The first pass was made in February and, if possible, a second one was made in June.

With the use of the tractor, the planting grid was increased once again and it was in the seventies when the use of machinery gained wide acceptance over horse-drawn equipment.

Manual work on the vines started in early winter with pruning, initially with “podones” or iron pruning knives and, years later, with the two-handed, wooden handle secateurs. The vines were head-trained and were lower in height than present day ones, with three arms of six and up to eight spurs. During the pruning season, the replanting was done by a technique known as layering, in which a new vine was formed by burying a cane shoot, still attached to the mother plant, leaving the tip of the cane above ground.

The vine was left to grow at will, given that the authors observed that the thinning and suckering tasks were infrequent and shoot tipping was rarely performed. All the same, some days before the harvest, hedging was performed in order to facilitate the movement of the harvesters between the vines. The reason for not thinning the vines was that this was unnecessary when the pruning was correctly done, however if they had time they would remove the root shoots or suckers.

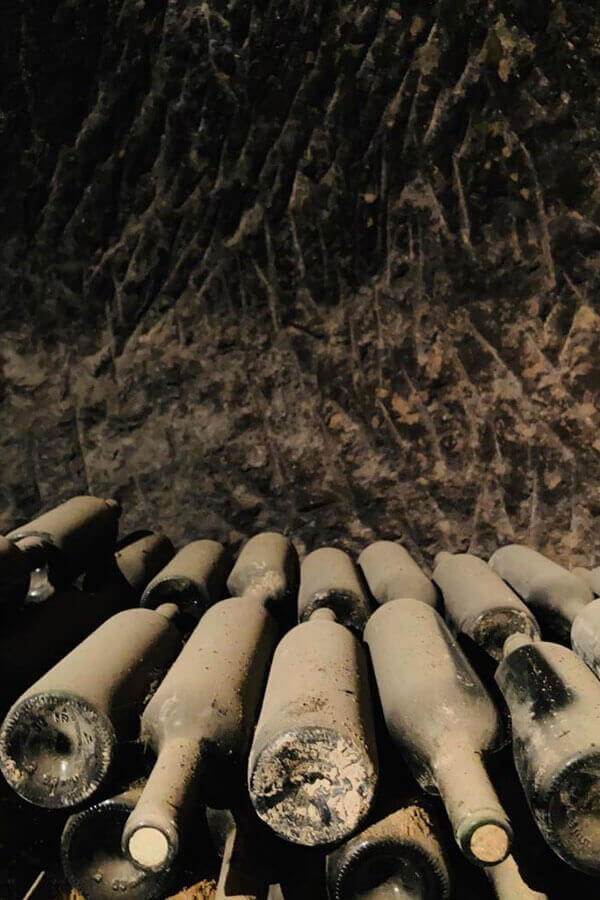

The most traditional way of harvesting was with a bill hook and the fruit was collected in woven chestnut baskets, made by local basketmakers and cane makers. They also made large, deep wicker baskets that could hold up to seventy kilos of grapes, which were crushed by treading, although part of the grape must was sometimes lost. Table grapes were grown and picked in August, particularly the earliest white grapes, while the remaining grapes were taken in oval-shaped wooden containers that were made in Muchante. A cart could transport up to ten wooden containers and the mules pulling the load would take the cart right up to the winery door, where the containers would be unloaded by hand and taken to the fermentation vat. Given that some of the roads were narrow, an ingenious system comprising cement conduits was created in Quel, running from the top of the district to the winery below. These conduits were known as “luceras” and they also served to remove the carbon dioxide produced during fermentation, known as “tufo” (strong smell). Barco and Elías also pointed out that these conduits were not an application that was exclusive to the Barrio de Bodegas winery district of Quel, given that in Horche, a town in Guadalajara, the traditional caves featured a system whereby the grapes were unloaded through a series of holes drilled in the land and which led to the vat at the bottom. This system also served to ventilate the winery and avoid the dreaded “tufo”.

///history

Bodega quarter of Quel

A historical gem

///history

Viticulture in Quel

Earliest origins

///history

Vine cultivation in Quel

The poorest soils for the vineyard

///history

Quel castle

A castle, a stone vat and a winery

///history

Winery districts in La Rioja

Culture, history, heritage and wine